Published on: 12/19/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

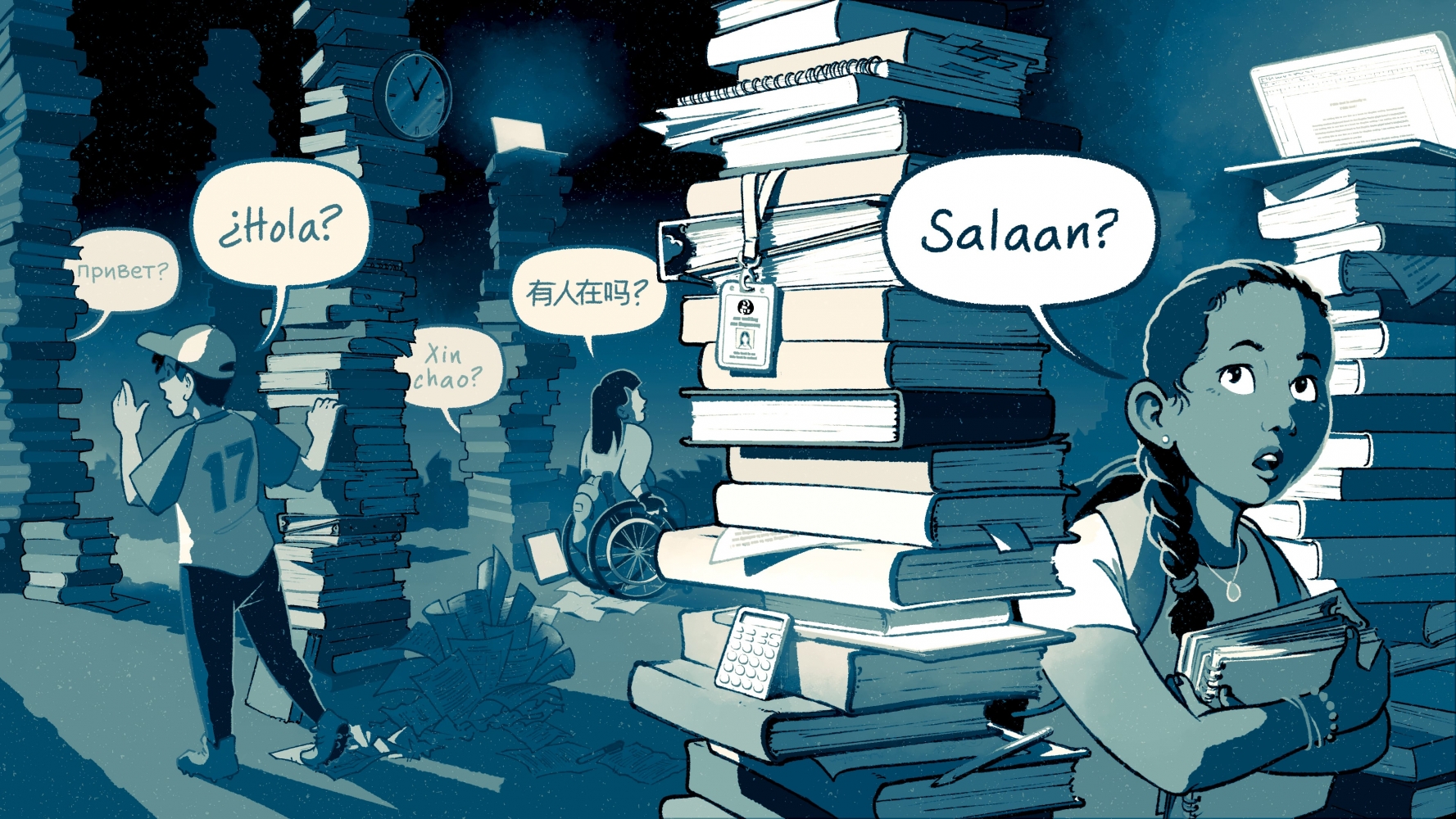

When Nancy’s family moved from Mexico to Oregon, she barely spoke any English. So when the youngest of her three sons was identified with a disability, she needed help.

“They told me that we needed to get together to talk about the services that he would receive,” Nancy recalled through an interpreter. OPB is only using Nancy’s first name at her request to protect her family’s safety. “I needed an interpreter or someone who would help me understand.”

That’s when Nancy began working with Ariel Lavandera, the then-Spanish language specialist for Portland Public Schools’ Language Access Services team.

Under a civil rights settlement nearly a decade and a half ago, PPS agreed to improve supports for families like Nancy’s who speak languages other than English.

And it did that, in part, by leaning heavily on a small group of multilingual staff who built relationships within foreign-language communities and developed expertise in complex aspects of education policy, from special education to discipline.

“In all of these meetings where I was working with Ariel as my interpreter, I could understand every point that was being made,” Nancy said. The two worked together for nine years. “I felt very secure working with someone who I already knew.”

But in the most recent round of multi-million dollar budget cuts, PPS eliminated that team. The district says it can provide the same service by relying on less expensive staff and outside vendors.

However, many families who rely on these services — the very people who were supposed to be helped by the civil rights agreement — say the district’s new approach isn’t working for them.

“Mr. Ariel would call… to let us know about any updates or any important things that would happen regarding the school,” Nancy said. “I don’t get those calls anymore.”

The Language Access Services, or LAS, team was part of the district’s central communications office and consisted of seven positions — specialists and support staff — responsible for interpreting and translating Spanish, Vietnamese, Chinese, Russian and Somali. Those are the five most common languages in the district, but they’re only a fraction of the 145 different languages spoken by PPS families.

The staff worked out of different school buildings, often attending sensitive meetings, including discipline hearings and discussions of Individualized Education Programs (IEP) for students with disabilities. They also managed the district’s language line, a mandated resource for non-English-speaking families.

The Language Access Services team was one of a handful of language teams in the district. PPS also has community agents, contracted vendors and employees housed in the district’s special education department.

The district declined interview requests for this story because it’s in an ongoing dispute over language staff. In public statements, PPS officials have said the different groups supporting foreign-language families are redundant.

But Lavandera said LAS staffers are more specialized than community agents and contractors, particularly in high-stakes interpretation and translation, when specific knowledge and terminology are key.

He also said LAS staff were better able to maintain relationships with families, and they received high-level training as members of the American Translators Association.

“Many of us, myself included, served first as community agents for years and later transitioned into the LAS role,” Lavandera said. “That shift reflected a move from general community support to a highly specialized language access role designed to meet legal and educational requirements.”

Now, that team is gone.

Portland Public Schools faced a more than $40 million budget deficit this past spring. That’s on top of a $30 million shortfall the year before — an example of the fiscal challenges faced by districts across Oregon and the country, due to federal cuts, enrollment declines and rising costs.

PPS used the other interpretation services before cutting the LAS team. There are more contractors or on-staff community agents available, and they can be much cheaper.

More than 2,200 interpretation requests and 900 translation requests were reported in the district’s Language Access Report to the school board, covering the period from August 2024 to April 2025.

The five LAS specialists completed about the same share of translation requests as outside vendors and did fewer of the verbal interpretations. But the LAS team costs roughly 65% more.

The district was adamant this spring that no new services were being contracted out because of the cuts and that it remains fully compliant with the Civil Rights Act.

“The change is in shifting fully to a model that already exists,” district staff told the school board, “rather than funding duplicative internal roles that, based on data, were underutilized.”

Members of the small, now-dismantled team argue that the district’s portrayal of their work is, at best, misinformed and, at worst, deceptive.

They maintain that the numbers presented to the school board omitted important data. And with language specialists making around $25 per hour, as one former worker put it, in a district of more than 8,000 employees, they don’t see their salaries breaking the district’s bank.

“We work with the families when they [are] kids, and then when they are adults and have kids,” Lavandera said, his voice catching. “That’s irreplaceable.”

Families face confusion, shame, frustration

Trang Nguyen has two children in the district. For her, having the help of Vietnamese language specialist ThanhHa Nguyen was invaluable when her son was struggling with his speech.

“I have twins, so when Miss Ha talked to my children, she found out that my son has a problem pronouncing the letter ‘r,’ ” Trang gave as an example through an interpreter. “So, she discussed this with me and gave me some advice on how to get help and support for my son.

“Every time I have any concern or question, she always gives me the answer,” she said.

But Trang considers herself one of the lucky ones — she got support from ThanhHa when her children were still little. She and other parents who’ve worked with the LAS team are worried about what might happen to new families.

“Those parents who need the service in school but do not speak English enough, they might need to seek out another parent to help, or they need to find another way ... like go to the library,” Trang said. “It’s a longer way to get help.”

Several families argue that the contract interpreters are less consistent or qualified, and they haven’t built trust with affected communities.

It’s only been a few months with the new system, but families and staff shared anecdotes of different interpreters being called for each meeting. Sometimes they don’t show up, and there’s little to no oversight to report that. It also seems there’s been more reliance on interpreting by phone, rather than in person, which they said makes understanding things much harder.

The change has hurt some more than others.

Kelly Ma has two children in the district as well. She speaks some English but has needed the help of Chinese language specialist Yvonne Liao for her oldest.

Ma’s son, who goes to Woodstock Elementary School, is on the autism spectrum. Ma was still trying to understand the U.S. education system when she realized her family needed help.

“I don’t know what to do at the beginning, when my kid doesn’t … follow the step, what the teacher asked you to do,” Ma recalled to OPB. “I was kind of nervous. What’s wrong with my son?”

“This year, since the school doesn’t provide an interpreter or interpretation, the communication becomes harder,” Ma said through an interpreter. “Sometimes, we just don’t know who to find. For those Chinese families who do not speak any English, they just don’t know what to say.”

Ma said she doesn’t know how to connect with the district’s community agents, and the language line is no longer a valid option.

“In the past, even when nobody answered the call, you would get a message,” she said. “Now, the number is still there, but there’s no one answering calls anymore.”

The language line was for families who don’t speak English to get help on everything from reporting an absence to setting up meetings or getting referred to another resource.

“Any issue that the family could have with their kids in the school,” Lavandera said, “they will call the language line in their language, and they get help from us.”

The language line resulted from a series of complaints. In January 2011, PPS received notice from the Western Division of the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights regarding three complaints against the district for failure to provide adequate interpretation and translation for families in their native languages.

That April, the district agreed with the civil rights office to launch the PPS Language Line, among other changes.

LAS interpreters used to answer the line and return messages.

Now, Lavandera said that when someone calls the district’s main number — and they’re prompted by Lavandera’s recorded voice to press two for Spanish, for example — they get a message saying the service is no longer available.

There is still information about multilingual phone support on the district’s website, but critics argue it’s not regularly operated, if at all.

Lavandera said new district leaders haven’t bothered to learn about the key role of the language line.

“It’s important because these people need help. I mean, that’s the human part,” Lavandera said. “But it’s important because it’s a [mandate]. And we are not providing that service anymore.”

This isn’t the first time the LAS team has faced cuts.

Lavandera remembered back in 2017 when the district “unassigned” the entire department, which was then called Translation and Interpretation Services, or TIS.

That move, he said, was another example of a new person taking over the department and not knowing what all they did. Families and special education teachers, in particular, were upset and made their feelings known. The district reinstated the department a couple of months later.

“This is very similar,” Lavandera said. “A new manager comes from outside who doesn’t know anything about what we do, and she listened to the wrong people, and she made a wrong decision.”

But this time, he’s not so sure it will be fixed.

“I’ve been working for Portland Public Schools for 23 years. I never thought I would be unemployed like this,” he said. “I’m rethinking my future.”

‘The only people who are suffering are the underserved communities’

Riyaleh Said started working with PPS in the early 2000s, based at Jackson Middle School as the Somali language specialist.

“The only people who are suffering are the underserved communities,” he said. “And we know exactly, you know, the current politics and the current situation back home. This is the [time] they need our service [the most].”

Both Said and Lavandera worked as community agents before becoming language access specialists. They say handing over their work to community agents comes with a big problem: some underserved families, including those in Somali and Russian-speaking communities, don’t have an agent right now.

“They say that they have community agents doing the same thing,” Lavandera said. “But it’s not true.”

Liao was the Chinese language specialist for five years, but, like Said, has worked with the district for about 20. She said the relationship she had with families was crucial — and communication went both ways.

The parents might ask Liao, “How is Jaden doing in school?” Then Liao would contact the teacher and report back to the family, “Oh, Jaden didn’t eat much lunch today,” she gave as an example. Liao also made a point to check in with the kids when visiting their schools.

“In our culture, if the kid is not listening well, following well, behaving well, the parents feel shame,” she said. “So, they don’t trust others.”

Liao previously worked for PPS as an educational assistant. She applied to do that again, since being laid off, but didn’t get the job.

District officials told the school board in the spring that requests made to LAS staff for weekend or evening services were “frequently declined or canceled at the last minute.”

“In several recent cases,” they said, “assignments for after-hours events were either ignored or turned down without backup. Vendors, by contrast, consistently fill these time slots and provide reliable coverage.”

Liao countered: “We never refuse work unless we are sick. We always accept.” She let out a deflated laugh as she said, “I still don’t quite … accept that we are not working for our families.”

Union pushes back

Since being laid off, Vietnamese specialist ThanhHa Nguyen has been working as a special education assistant.

She took the job to have health insurance. But the job, she said, is very tiring. “It’s very, very hard.”

ThanhHa has been learning even more about special education, but she said she doesn’t have a chance to return to the LAS office to bring that expertise back to the families she’d been supporting.

“I love my job a lot,” she said. “I cry a lot, like, ‘What’s going on?’”

The Portland Federation of School Professionals represents classified workers in the district, including the language access specialists. Since the workers were laid off in the spring, the union has been fighting, including by filing a grievance against the district.

Their main argument is that the district is violating their contract by laying off protected staff and prioritizing contracted work instead. PFSP has filed multiple grievances with the district, accusing it of prioritizing contracted work over union workers in addition to LAS.

“There’s no way that five PPS workers can handle all of the translation efforts of the district, right?” said Amy Krivda, the secretary for PFSP and a special education worker. “So, we’re not trying to make an argument that the district cannot provide any contractors, but it does need to be supplemental.”

District leaders maintain that all families’ interpretive needs are being met, but they declined to comment directly for this story, citing district policy about the pending grievance. Through mid-December, the district has repeatedly denied the PFSP grievance.

“It would be great if the district could look at their own history and see … the things that they’ve already done, and that we as a union have already done and fought for, instead of making the same mistakes again,” Krivda said.

The union’s grievance calls for the LAS employees to be rehired and receive backpay. But PPS is preparing for another round of multi-million-dollar budget cuts in the new year, leading to the question of whether a favorable ruling for the union might be a short-lived victory.

Nicci Kaufman, a field representative for PFSP, said the district’s excuses for these cuts don’t line up with its values, particularly as U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers are focused on immigrant families.

“To cut these services that are such a vital part of how multilingual and diverse families connect with their right as humans and as Americans to access public education, to kind of isolate them further in this political climate,” Kaufman said, “it just goes against everything that the district has said.”

The union now needs to decide whether to bring the state in for arbitration.

Editor’s Note: OPB used interpretive services through Passport to Languages to interview families for this story.

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/12/19/portland-public-schools-oregon-language-access-services/

Other Related News

12/19/2025

Jinju Patisserie the North Portland pastry and bonbon shop that won a James Beard award as...

12/19/2025

Multnomah Countys jail health director departed from the role after less than a year on th...

12/19/2025

If Congress and parking garage planners had gotten their way Oregons oldest public buildin...

12/19/2025

Dressed as the pregnant Virgin Mary and her husband Joseph a couple moves from door to doo...

12/19/2025