Published on: 01/17/2026

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

Talented and ambitious from a young age, Justin Hampton happened to be the right person in the right place at the right time.

Hampton was a Medford high school kid who grew up in the ’80s on a steady diet of pop culture, Marvel Comics and punk rock. Hampton had just graduated from art school in Seattle when the grunge music phenomenon was about to break, with bands like Nirvana, Soundgarden and Pearl Jam putting Northwest music on the global stage and defining the sound of rock throughout the 1990s.

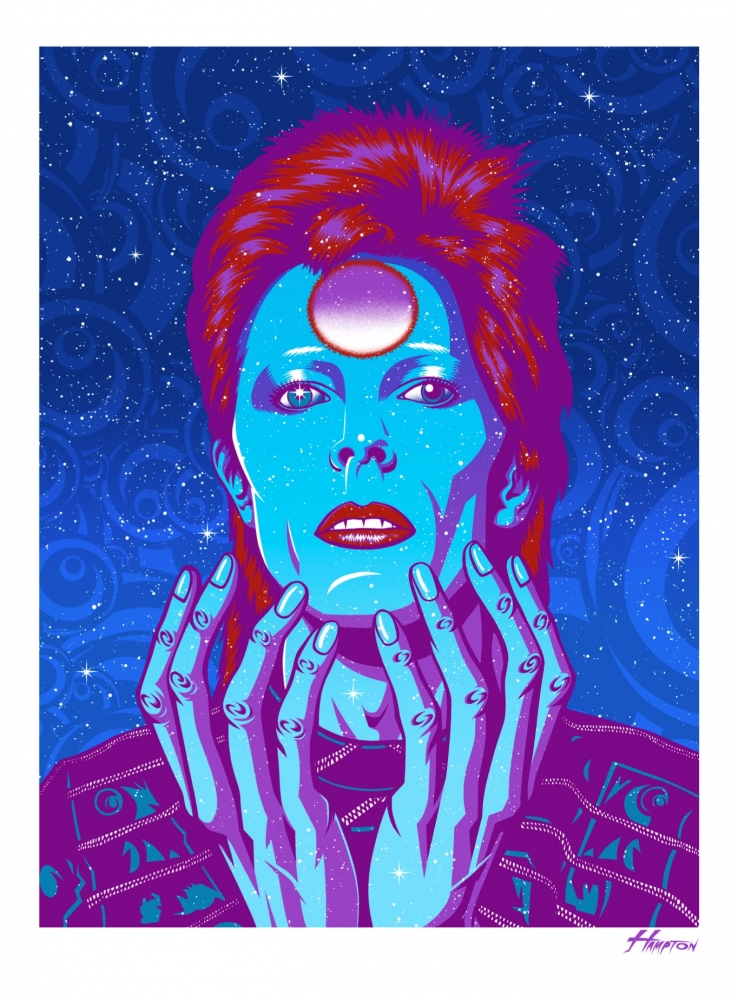

Hampton’s vivid, multicolored original screenprints depict some of rock’s most famous pop icons with humor, visual irony, and a deep love for the music and culture. From his own spin on iconic Norman Rockwell paintings for Pearl Jam to David Bowie as a glam Messiah printed on holographic foil, Hampton’s work stands out.

“There’s a lot that goes into it,” Hampton said. “It’s a very tactile artisan type of craft in that it’s all hand done. The colors are custom mixed by hand. Everything is signed and numbered, limited editions.”

Roots of a rock poster atist

Hampton grew up in Medford, Oregon.

“My early inspirations in small town America was basically pop culture — TV, movies, but also comic books," Hampton said. “As a little guy it kind of really opened up my mind, and I started copying these things as a kid. Comic book art, album art or whatever.”

At 14 years old, Hampton began sending art samples to Marvel Comics with dreams of being hired to draw his favorite superheroes. But as time rolled by and high school came to a close, the comics industry remained elusive.

Eager to get out of Medford, Hampton moved to Seattle in 1987 to attend art school.

Hampton arrived in Seattle with no idea anything was happening in the music scene, but it wasn’t long before he was exposed to the burgeoning Seattle sound at the dawn of the grunge era.

“It was just a weird confluence of events that brought me to this moment, experiencing all these different bands,” he said.

In the early ’90s, one of the main ways bands got the word out about shows was by putting up flyers. They were usually 11 x 17 inches — the largest size bands could afford at Kinko’s, their go-to late-night spot for DIY promo posters and handbills.

“In my last quarter of school, I was asked to do this final thing for a typography class,” Hampton said.

Hampton already had plans to see a Nirvana show when inspiration struck. He’d seen flyers on telephone poles around town and thought, why not just make my own poster?

Hampton took the initiative without any official permission and got to work. “I designed it and I put it up. That’s literally the first flyer that I ever designed. Just my own guerilla style Nirvana flyer.”

Right out of art school in 1990, Hampton began illustrating for Seattle’s monthly music magazine “The Rocket.”

“It was kind of like the zine of the grunge era, and so I became a regular contributor,” Hampton said.

Hampton still had his eye on comic book work as new alternative indie publishers began gaining national attention, including Fantagraphics Books.

“The underground [comics] scene was really kind of taking off, so I did comic book work,” he said. “I eventually wound up being an inker for a bunch of different companies. I became a colorist. So I just kinda kept going with whichever thing kind of took off.”

At the same time, bands and local promoters were asking Hampton to make flyers for their shows.

“It was like 25 bucks and like, you know, some free beer that night at the show or something, you know, maybe food,” he said. “I never really thought of myself as becoming a poster artist. In fact, I didn’t think that it was possible to be a working poster artist and make money.”

Crackdown: The Seattle no-poster ban

As bands grew more popular, local telephone poles became bulging layers of overlapping posters. Then, in 1994, a no-poster ban went into effect.

“Seattle City Council had decided that basically flyers were not beautiful and that they were like making the city ugly,” Hampton said. “And so they made it a law that it was illegal to put up flyers.”

The new law radically limited where bands could promote their events, leaving only specific spaces like record shops, grocery stores, and the windows of small businesses willing to give permission.

“At the same time, Frank Kozik and Coop and all these guys had been doing posters in California, screenprints," he said. “And that was getting traction nationally. That became a thing in Seattle too.”

Promoters realized they needed to make a stronger visual impact if posters were only going to be seen in a handful of locations.

“I started getting commissioned to do multiple colors on screenprints,” Hampton said. “And then people were like, hey, I saw that poster. I’d love to buy one from you.”

Over time, the grunge-era style of Hampton’s work began to evolve.

“The grunge phase was more kind of raw, which was influenced by, you know, punk fliers and more underground comic books,” he said. “But a more edgy kind of look, you know, and then, and then my style got really polished, by the mid ’90s.”

In 1995, Hampton made his first major national splash with a poster for PJ Harvey. “It was that moment that really kind of put me on the map.”

Around that time, Hampton began noticing artists creating their own websites to sell art.

“I made it my mission to build a website and get my stuff up,” he said. “I started talking to local printers that were like, you can pay me on the backside after you sell the posters.”

That shift made it viable for Hampton to self-publish his own screenprinted posters and sell directly to collectors.

“That’s when things really started clicking. I’d say around 2002, I was really taking off in the world of becoming like completely self-sufficient,” Hampton said. “It was a pretty amazing time, for sure.”

After more than 20 years in Seattle, Hampton could see gentrification and change coming. It was a new era for the city — and for the music scene he’d come of age in.

“I loved the, you know, late ‘80s through the ‘90s Seattle. And watching it disappear was kinda hard.”

In the late 2000s, Hampton decided to move to Portland to be closer to his family in Medford. “I now had a young boy, Miles. And, uh, it just made sense to do something different.”

Reflecting back, Hampton sees himself as part of the old guard. “It’s a different time and place … it’s definitely a new era, a new time in my life for sure.”

‘Visual Feast’

Hampton looks back fondly on being part of a singular time and place in music history during the late ’80s and early ’90s, but he doesn’t want his work to be defined solely by that era.

“It was definitely, you know, kind of where I cut my teeth was in that era,” he said. “But, you know, there’s a whole other 30-plus years of other work too.”

Six years ago, Hampton set out to self-publish a coffee-table book of his artwork titled “Visual Feast.” With the help of a successful crowdfunding campaign, the 444-page hardbound edition spans his career and features full-color reproductions of poster art from the late ’80s to the present.

“There’s photos, there’s sketches. Tales of hanging out with different band members. I really delved deep into the relationships that I’ve had with promoters and other artists,” he said. “It’s not just a picture book. It’s definitely a storybook too.”

Holding the line on human-made art

Hampton feels lucky to still be doing what he loves, though he concedes that competition is fierce, with a growing number of younger poster artists and new technological threats facing working artists.

In early 2024, the generative AI company Midjourney — known for enabling users to create visual art through text-based prompts — released a list of 16,000 artists whose work had been used to train its AI models.

Curious, Hampton checked the list to see if his name appeared. He was stunned to find himself included among a notable who’s who of celebrated artists, including Rockwell, Warhol, Banksy and Picasso.

“I remember at first, kind of like being, oh! It was a weird, like, combination of, like, you know, it’s impressive that you’re known enough to have been included,” Hampton said, but his reaction soon changed.

“That became really kind of like, yeah, angering that they were doing that, but they were just freely feeding this engine, everything that they could to build this style.”

Hampton admits he has no idea where prompted AI art will ultimately lead or how it will affect future generations of artists. For now, however, he believes original screenprinted poster art remains a safe haven — one where artists can continue handcrafting images and finding collectors who value the unmistakable human touch.

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2026/01/17/justin-hampton-poster-art-seattle-portland/

Other Related News

01/17/2026

Portland State Universitys Homelessness Research amp Action Collaborative HRAC has release...

01/17/2026

A freezing fog advisory was issued by the National Weather Service on Saturday at 749 am i...

01/17/2026

On Saturday at 749 am a freezing fog advisory was issued by the National Weather Service i...

01/17/2026

Twenty-five years ago a very different-looking newspaper celebrated its 150th anniversary

01/17/2026