Published on: 06/02/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

David “DJ” Jennings sat in the front row of his eighth-grade English class at Waldo Middle School in Salem. He’s tall for a 13-year-old — over six feet — so his bent legs stick out from under the desk.

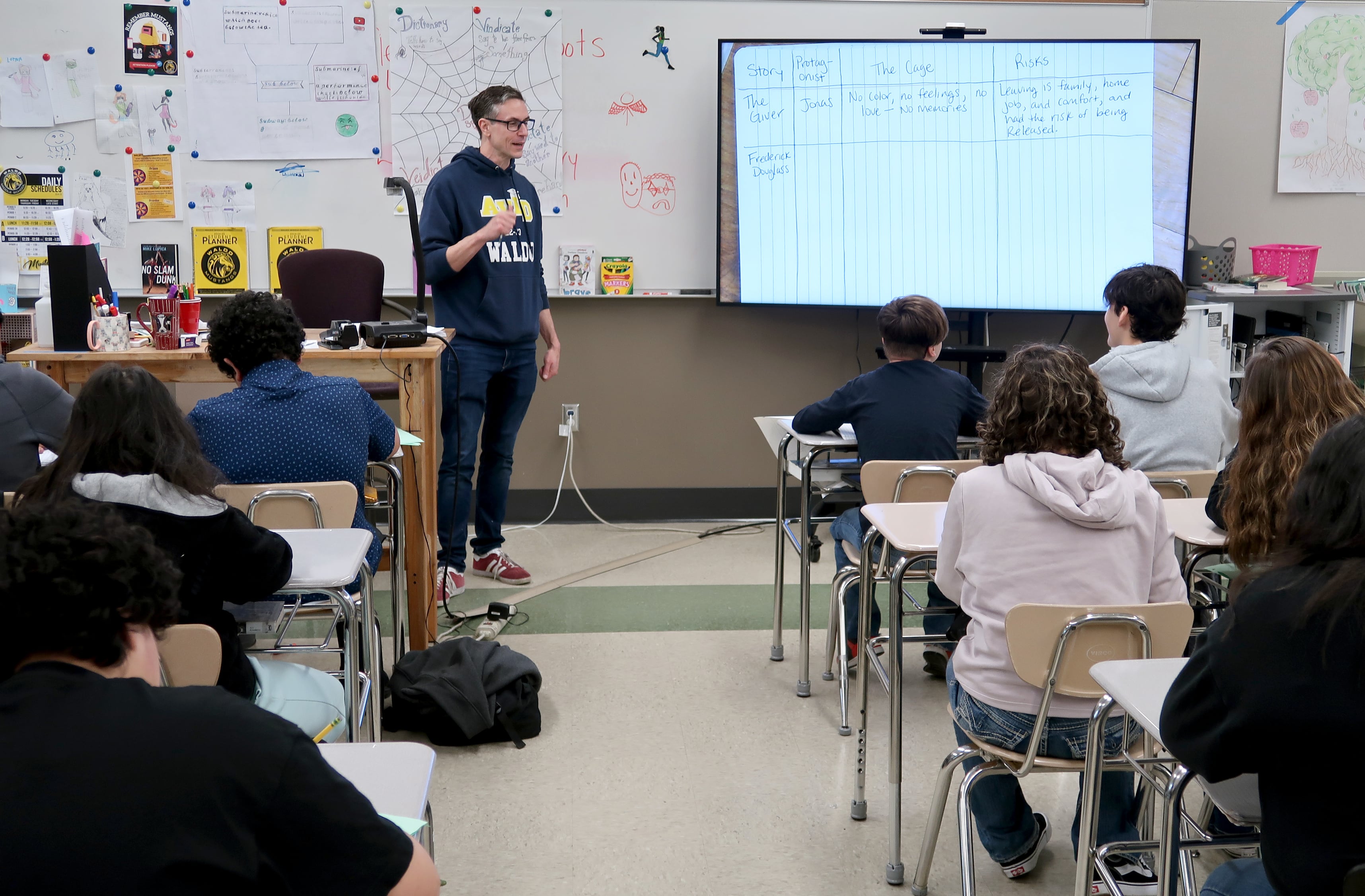

Despite it being the first class period on a Monday, DJ listened intently. His gaze darted from his notebook to the projector in front of him as he matched his notes with his teacher’s. The class was plotting out the characters and their obstacles from recent stories they’ve read.

“I want you to remember a particular poem that we read at the beginning of this unit,” teacher David Mann said to the class. “It was called, ‘I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings.’ Can anybody remind me what that poem was about?”

DJ raised his hand, as he did for nearly every question throughout the exercise. “Like, a caged bird,” he said, “but metaphorically.”

“Like a caged bird, metaphorically,” Mann repeated. “What do you mean by ‘metaphorically?’”

DJ didn’t remember the story entirely, but he said the person was going through something, and they wrote a poem about it.

“Let’s talk about, then, what is the stuff that they are going through?” Mann said. “You’re exactly right, David. Thank you.”

Those who know DJ probably know that he loves Pokémon, playing video games and watching YouTube. He’s a fan of the Portland Trail Blazers and Cocoa Pebbles cereal. He wants to play pro basketball when he grows up.

But what many might not know is that until this year, DJ was part of the most restrictive learning environment in Salem-Keizer Public Schools — the Behavior Intervention Center, known as BIC. BIC serves students with disabilities who have significant levels of aggression. Until this school year, DJ fell into that category.

“It feels, like, more normal,” DJ said about being at Waldo. “‘Cause the last time [I was in a normal school setting], I was, like, in maybe second, third grade.”

When asked why he’d spent so long outside of traditional classrooms, DJ responded, “Probably because of my behavior.”

DJ has an emotional behavior disability. He hasn’t always controlled some of his more negative actions.

Being at BIC wasn’t a negative experience for DJ. He said he had fun there. He liked the staff, and he sometimes got to watch shows like “The Flash” during lunch. But partway through this school year, with support from district staff and his care home, DJ transitioned to Waldo and into a more traditional general education setting with his peers, including Mann’s English class.

That’s considered a major success. It means DJ and his classmates get more academic and social opportunities. Educators say he can feel seen, heard and valued in a way that’s much harder in a restrictive or removed environment. And research shows inclusive classrooms can result in higher test scores and fewer disruptive behaviors, among other benefits. These things bring DJ’s chances of being disciplined down, and his chances of graduating up.

But to support students like DJ, school districts need three of the hottest commodities in education: people, time and expertise — all of which cost money. Tens of thousands of dollars per student per year.

One of the biggest challenges facing schools all over the country is how to pay for those high costs. A record number of students nationally receive special education services, yet resources and qualified staff are in short supply. Without enough money, kids’ needs may not get identified, and even if they do, they might not get the kinds of support they need.

Educators are fighting for more money at the district, state and federal levels. And though this year brings another budget season rife with reductions for many Oregon school districts, Salem-Keizer is in a unique position. They made major cuts last year that will help them avoid staff reductions this coming fall, and they’re making a distinct choice to invest their limited funds in more behavioral health and special education support for next year.

DJ’s transition to Waldo

This time last year, DJ was a different kid.

At least, that’s how it felt to educators like Aaron Johnson, the principal at BIC.

“He was very unsafe with his behaviors and self-harm — dangerous, physical aggression,” Johnson recalled. “He required multiple adults when he became escalated, to the point where restraint or seclusion was needed almost daily.”

Policy makers have worked for years to limit how frequently staff physically restrain or isolate students because, when used inappropriately or excessively, it can be harmful to children. But special education staff and administrators say it’s often needed to maintain safety.

“He required a lot of adult support,” Johnson said.

Things changed over the summer.

When DJ returned to school for the fall term, Johnson said he’d gotten taller, lost weight and was taking his medication consistently. He had dramatically reduced his screen time and was involved in his community. That was especially true where DJ lives — at a stabilization and crisis group home called SACU. The 24-hour crisis residential program operates under Oregon’s Office of Developmental Disabilities Services.

“When he started with us in September,” Johnson told OPB, “all of the staff were like, ‘Wow, this is a new kid.’”

Johnson credits the stabilization care home for the progress over the summer. But BIC helped continue it, so — after several weeks without incidents — DJ could transfer to Waldo Middle School.

DJ started at Waldo with an adult assigned to help him; he attended classes there only a couple of hours a day. Staff very quickly realized he was ready to transition full-time, and that he didn’t need as much one-on-one support. They were worried when he first arrived that he would be disruptive, but he wasn’t.

“I mean, it came sooner than any of us expected, because he was just so successful,” said Waldo Principal Ingrid Ceballos. “And he just loved it.”

Depending on their needs and individual plans, some students might have an instructional assistant or other adult who works with them or checks in with them throughout the day. Students may spend more time in separate special education classrooms than in their general education courses.

Ceballos said DJ has gotten to the point where he mostly navigates the school independently. He’s social, too. He has friends, is part of the after-school gaming club and goes to school dances.

“You wouldn’t know that he’s a student in one of our specialized programs, just by looking at him,” Ceballos said. “He’s integrated really well.”

DJ’s English teacher, Mann, seconded that. In fact, he didn’t know DJ’s background when he first joined his class.

DJ jumped right into the lessons. Mann laughed about a particular memory when DJ started in his class. They were discussing the novel, “The Giver,” by Lois Lowry. DJ had already read it.

“He was completely engaged in conversation, and I had to shush him down because he would become very excited when something was going to happen,” Mann said with a smile. “I’m like, ‘No spoilers!’”

Mann said DJ initially had a staff member with him in the classroom, but it was so unnecessary, Mann didn’t know what he was there for. That person quickly went away.

“I mean, he’s such an easy-to-work-with student,” Mann said. “If you were to interview any of the students in my class, they would have no idea about his background,” adding that they would say, “He’s just an enthusiastic, sweet, nice kid.”

The people, costs behind the scenes

Ideally, students stay at BIC for less than six months, but the average is closer to a year. To get students, like DJ, to a point where they can transition into their neighborhood schools, districts and programs need people, sometimes one to three adults for each kid, depending on their needs.

These workers — including teachers, social workers and behavior trainers — are highly qualified and trained, and have to be willing to deal with all kinds of behaviors.

“Our staff get hit, kicked, punched, bit, scratched, concussed all the time,” Principal Johnson said, “and they just come in with a smile on their face every day and do it again.”

This year, BIC has 23 total staff members. They’ve served 20 students this year in grades 1-12.

If more kids come to the center, they don’t get more staff, Johnson said, so the workers get spread thinner. Due to the nature of the job, the employees need to be paid more, he said, and there’s a high turnover rate.

“Our goal is to get the students to learn the skills they need to go back to a comprehensive setting,” he said, “whether it’s social emotional regulation or helping them with self-injurious behaviors or suicidal ideation.”

For students with acute behavioral health needs, individualized support can cost more than $60,000 per year per student, explained Chris Moore, the director of mental health and social-emotional learning for Salem-Keizer.

That’s the cost for many students in school-based, self-contained programs. By comparison, schools across Oregon received an average of about $18,730 per student in the 2022-23 school year, according to the latest available data.

For a student at a highly specialized program like BIC, the dollar figure multiplies to about $120,000 per year, per student.

The extra money pays for highly qualified staff, meetings after school, and the work to connect students’ families with community resources.

Johnson said it would be hard to replicate their work, but in an ideal situation, there would be a lot more behavior trainers to go into schools and provide more structure, accountability and routine.

“That would be life-changing for a lot of students,” he said.

Salem-Keizer is uniquely poised this year with its budget. Unlike many other major districts in Oregon, they aren’t expecting staffing cuts for next year.

In fact, the district plans to add around two dozen positions and invest more money for these services, including the continuation of $53 million budgeted for mental and behavioral health services and $118 million for special education.

Moore said the districts can’t do it all, saying it’s like being asked to provide $100 worth of services on a $20 budget. But they can’t let that get in the way of doing the best they can with what they get.

“DJ is a real-life success story because of the thoughtful investment of time, skill, energy, and care from dozens of educators and support staff committed to his healing and growth,” he said. “Without that investment, we communicate systemic indifference and perpetuate a level of harm that ripples throughout the school system year after year.”

A state and federal conversation

For decades, Oregon’s spending on special education has been artificially limited. The state provides additional funding for students in need of special education support, but it has capped that additional funding when the portion of students with disabilities exceeds 11% of the district’s total enrollment.

However, students receiving special education services statewide account for nearly 15% — more than 82,000 children in the 2023-24 school year. For some districts, that percentage is even higher.

The cap results in roughly 20,000 students not receiving funding for the services they need. School districts can apply for a cap waiver, but thousands of students are still left without adequate resources.

Eliminating the cap would help address a gap of more than $700 million per biennium in special education funding. As it stands now, individual districts are covering that gap themselves.

“The good news is that we have so many professionals in this district (and they are) not paying attention to that. They’re paying attention to the kiddo who’s in front of them,” Moore said. “But at the end of the day, if we want this investment to last and have the biggest impact, we need to resource it correctly at the state level.”

House Bill 2953, proposed to lawmakers this session, would remove Oregon’s cap on special education funding. Proponents of the bill have pointed out that there’s no other individual student subgroup that has a limit on how much money it can get from the state. Washington lawmakers removed their state’s special education cap this spring.

But with the end of the Oregon legislative session just weeks away, it’s unclear whether HB 2953 will make it out in time — a fate shared by other education spending priorities. Oregon lawmakers on Wednesday introduced a detailed K-12 spending proposal, which will have a direct effect on special education funding.

“When you look at how states invest in special education, we consistently find ourselves near the bottom of the list with another antiquated model,” Moore said. “This only makes a tough situation even harder.”

At the national level, President Donald Trump’s plans to close the U.S. Department of Education and have the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services oversee special education, among other decisions, will likely impact students with disabilities, too.

But the latest changes and threats only add to decades of federal underfunding.

Back in 1975, when Congress approved the Individuals with Disabilities in Education Act, or IDEA, the federal government promised schools it would cover 40% of the costs of special education.

“That promise has been broken, year after year,” Moore said. “Funding has never even managed to surpass the 18% mark and, in recent years, has averaged around 14%.”

Moore stressed that this isn’t just a line item in a budget. It means helping students like DJ learn and develop into independent adults.

These investments form the foundation for long-term community benefits, he said, including a more capable workforce, a communal sense of belonging, and significantly reduced stress on social services.

“We’re nurturing human potential,” Moore said. “We’re building a pathway to an accessible future where more people can contribute to society, lead fulfilling lives, and ultimately, need far less intensive and expensive support down the road.”

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/06/02/oregon-special-education-disabilities-salem-keizer-budget-behavior-intervention-bic/

Other Related News

06/04/2025

The final stage is set The softball state title games have their teams after Tuesdays semi...

06/04/2025

Melqua Road is closed in the 1700-block with a heavy law enforcement presence while negoti...

06/04/2025

Due to fire activity in the area of Euston Lane and Coyner Avenue the Deschutes County She...

06/04/2025

Manzo Negrete was identified as the drug trafficking cells leader after an investigation b...

06/04/2025