Published on: 08/20/2025

This news was posted by Oregon Today News

Description

MITCHELL, Ore. – Wildfires are a natural part of the landscape in much of Central and Eastern Oregon. But in recent years, they’ve proliferated. Large fires have torn through hundreds of thousands of acres of dense forest and grassland where cattle graze.

James “Jim Bob” Collins has seen the damage a wildfire can cause and the effects it has on the land after the smoke clears. Collins is a fourth generation rancher in Central Oregon.

He’s also the board chair for the Wheeler Soil and Water Conservation District. It’s an elected position, although he doesn’t get paid for it.

His district had worked for months to receive a $21 million grant from the U.S. Department of Agriculture that would have gone to wildfire mitigation in forests and rangelands. But this summer, just as wildfire season was starting, the government walked back on its offer in Wheeler County and across the state. All told $90 million worth of conservation work is on hold across Oregon.

That’s left ranchers like Collins and his neighbors, whose land bears the scars of last year’s fires, hoping the rest of this year’s wildfire season is uneventful, as he and the conservation district he serves explore new ways to pay for the work.

Wildfires on the rangeland

On an August morning, Collins is trekking up a steep hill on a rugged utility vehicle. He’s on the land his family has homesteaded for over a century, north of the Ochoco National Forest.

His cattle graze on dry grasses that grow in between areas of dense pine forest. There are also the occasional bunches of juniper trees.

As he climbs up, he points to the parts of the forest where pine trees have been thinned, which means they’re not as close together. The trees are a bit yellow but mostly green, and are apart enough that the sunlight gets through the undergrowth and there’s some grass.

“We can see some grasses are starting to come back in this, because it didn’t burn as hot,” he said.

But then he drives up some more, to an area that has not been managed recently, perhaps not for decades.

“We have a little bit of grass coming back in here, but this is going to take forever. I mean, that is fried. That is cooked. This is what happens when you don’t cut anything,” he said. “I’ve cried over this a bunch. It sucks.”

The ground is fried, as in burnt. Last year the Shoe Fly fire went through Collins’ ranch. The fire burned 27,000 acres of pine forest and brushland in Wheeler County.

It burned fast, and so hot that it left burn scars in some spots where little grass has grown a year later. On some slopes it’s left bare soil at risk of erosion if a heavy rain comes through. And it left swaths of scorched pine trees at risk of falling over.

Collins said leaving it like that could put this land at risk of even more damage if another wildfire comes through.

“These trees are going to become an issue,” he said. “They’re going to start falling over. When you have a bunch of trees laying dead on the ground, if you want to talk about ruining the soil, that’s a really good way to ruin the soil.”

A $21.2 million federally funded project through Collins’ conservation district was going to help 92 producers in the Middle John Day Basin with that. It’s called the Greater Waterman Landscape Resiliency Project. The project was funded through a program called the Regional Conservation Partnership Program.

The district was going to work with those producers to cut, or thin dense forests that hadn’t burned yet. And it would have cleaned up some of the pine that burned, to encourage native grasses to grow back and prevent that burned timber from catching fire if another wildfire came through.

“What we were looking to do was bring the forest to a healthy stand again, which in turn fights against wildfire risk,” said Cassi Newton, the manager at the Wheeler Soil and Water Conservation District. “The whole focus of our project was fire resiliency.”

The district was also looking to do sagebrush habitat management, or reducing young Western juniper trees. Newton said although those trees are native to much of Oregon’s high desert, they have encroached into grasslands, and wet areas along streams and rivers, crowding out native species. They also suck up a lot of water from the ground.

“A huge factor that has contributed to that is the suppression of fire,” said Newton.

An unplanned pause

Much of that work is on pause now. Just before the district was finishing up agreements with the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the government withdrew its funding offer.

The USDA’s Natural Resources Conservation Service — a department under the umbrella of the USDA — did not respond to questions from OPB about why it backed out.

But an official with that department sent an email to the conservation district on June 11.

“NRCS regrets to inform you that the conditional offer to award is hereby rescinded as the agency is not moving forward with any new awards using the supplemental funding provided by the Inflation Reduction Act at this time.” read the email.

The email did not contain any further information about its withdrawal of the offer.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, passed under the Biden administration, was dubbed one of the biggest climate investments in the country’s history. It directed billions of dollars to clean energy, climate action and agricultural conservation programs.

But the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the budget bill backed by President Donald Trump, reversed many of those investments. Across Oregon, and across the country, many clean energy and climate action projects have been halted or scaled back.

U.S. Rep. Cliff Bentz, a Republican who represents Wheeler County and many other rural communities in Oregon, did not respond to a request to comment on the cut to the wildfire resiliency project.

“We were looking forward to it,” Collins said. “It was a big thing to utilize those funds for [forest] stands exactly like these because it had to have help to get it to get it healthy and, and to make it fire resilient.”

Collins said he wishes he had a chance to plead his case to the federal government.

“It is a good project. It’s a needed project that needs to happen,” he said. “It is so important to this region that it’s just financially not viable to manage timber here.”

Four other conservation projects across Oregon also lost federal funding, totaling $90 million worth of conservation work directed toward wildfire mitigation or habitat restoration.

Why farmers and ranchers work with conservation districts

There’s a reason why farmers and ranchers work with their local conservation districts to do this work: These districts connect producers with conservation programs, grants and funding to tackle projects they can’t afford on their own — often projects that have benefits beyond just an individual ranch or farm.

It’s work that’s been happening since the Dust Bowl era nearly a century ago.

“If you’re talking, out of pocket, if you’re gonna thin your timber ground and it was gonna cost you $1,200 bucks an acre… to thin it? people aren’t gonna do it,” said Jere Hamel. He runs a 38,000 acre ranch with his brother in Wheeler County. He’s also Collins’ neighbor.

Like in any business, ranchers take on a lot of financial risk. They could get wiped out by a natural disaster or a down market. They can’t always afford to improve or restore forest or grass land, Hamel said.

“People that are trying to make a living, that’s their sole source of income, it’s cattle,” he said. “I mean, yeah, the cattle market these last couple of years has been good, but previous to this. I mean, it was hard to break even. It’s not an easy business”

Hamel was one of the producers that had signed up to work with the local conservation district on the Greater Waterman Landscape Resiliency Project.

He said the funding getting axed was unfortunate.

“Healthy forests make healthy people,” he said. “It’s a big full circle of life here that we’re trying to create and we’re trying to promote and we’re trying to protect.”

Newton said the reduced funding doesn’t stop the work they do. There are other smaller conservation projects the group manages. But it means they’re able to do less.

“There’s less money and more competition,” she said. “It’s a very fragile situation right now with the federal funding where it’s at, but it’s still moving forward.”

Other conservation groups that also had their federal funds taken back will likely apply for the same pot of money through other sources, like state conservation programs, which are limited.

A ripple effect across rural communities

Newton said there’s more that is lost when this money gets taken away.

“There are just so many different aspects of this project that were beyond just the conservation practices hitting the ground,” she said.

That’s because that money eventually makes its way to people that get contracted to do these jobs, and then the local hardware store and the grocery store.

“Joe Smith off the street isn’t going to care if George is doing land management on his property, right?” Newton said. “But through contracting and bringing the money to the small rural communities, it’s allowing the communities to stay viable.”

Newton said the conservation district will try to get the project funded again. But it likely won’t receive as much money as the original award, which means, it will be able to cover less land.

Without that money, Jim Bob Collins said some ranchers won’t be able to prepare their land for wildfires if or when they come.

“If you don’t have the money, I mean, there’s nothing you can really do except just hold on and pray,” he said.

If anything, the risk gets pushed out.

“What happens by not funding this project now means that this work is pushed off another year,” he said. “So far we’re coming into the heart of fire season for the most part.”

It would be nice if no big wildfires came through, Collins said.

News Source : https://www.opb.org/article/2025/08/20/central-oregon-ranchers-federal-funding-delays-wildfire-resilience-projects/

Other Related News

08/21/2025

Richard Simms Jr and Nicole Lashawn Davis had been living together but were estranged at t...

08/21/2025

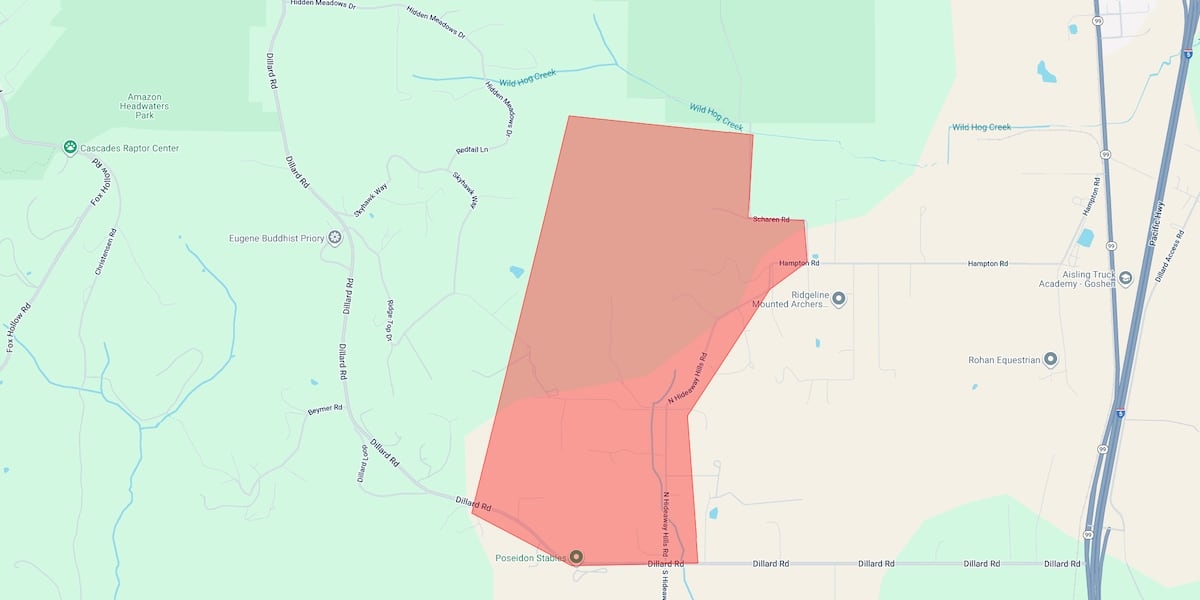

The Lane County Sheriffs Office issued Level 3 Go Now evacuation orders due to a wildfire ...

08/21/2025

Acting ICE Director Todd Lyons said federal immigration authorities plan to flood Boston i...

08/21/2025

Ethan Foltz 22 of Eugene allegedly ran botnet that reportedly targeted X formerly Twitter ...

08/21/2025